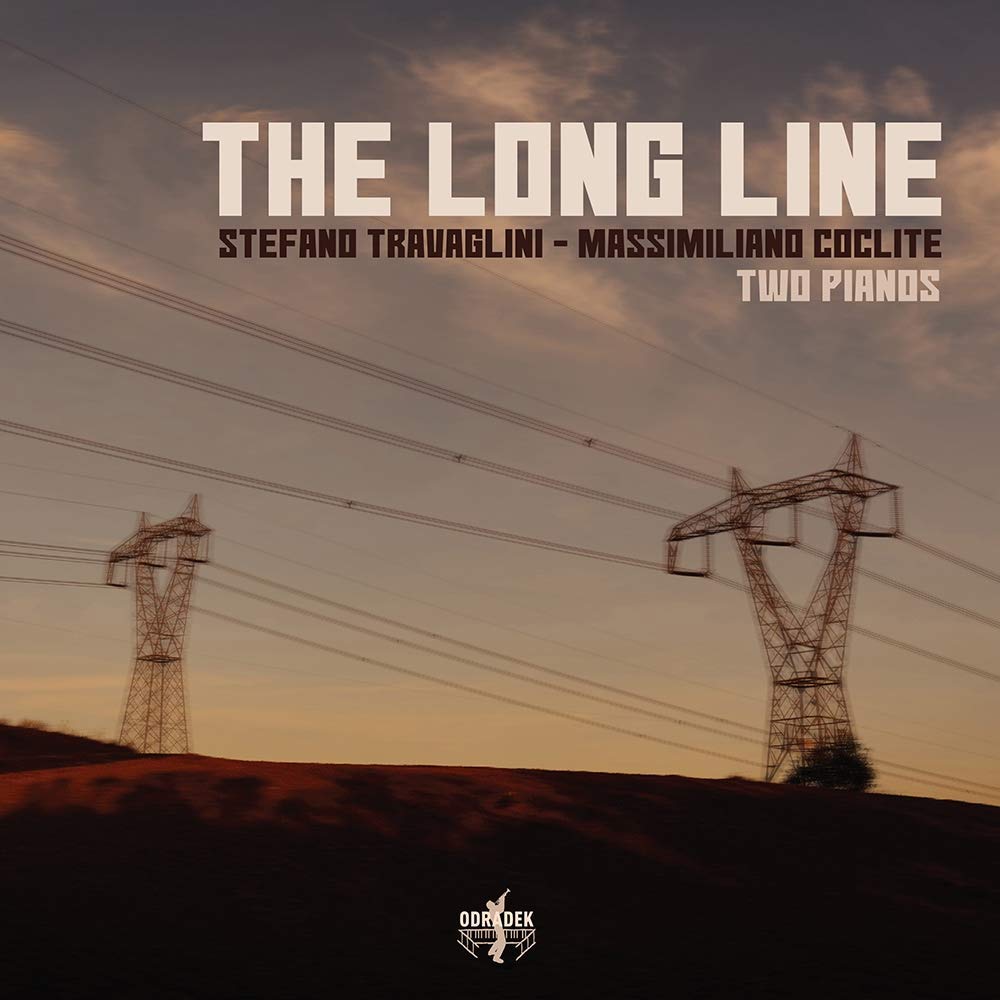

THE LONG LINE – Two Pianos (2019)

Stefano Travaglini & Massimiliano Coclite

Published by Odradek Records

LINER NOTES

A first hearing of the music on this album prompted thoughts about two issues in particular: the nature of improvisation, and the porous nature of the boundaries between jazz (and free improv) and classical music. Stefano and Max readily acknowledge the inspiration they have derived from Hindemith, Copland, Stravinsky and the English Tudor composer John Bull on some of the pieces on this album, and there are sometimes Baroque echoes, including lines which evoke J.S. Bach in the crystalline beauty of Mythos and, before it develops into a spikier phase, Garden of Delights, bookended by engaging, dancing opening and concluding passages.

A rigid barrier between composition and improvisation would have seemed a little odd to artists and audiences prior to the second half of the 19th century, when the dictatorial power of celebrity conductors and composers began to take hold. Concerto cadenzas had originally been improvised, but as the 19th century wore on composers were less and less willing to trust to the initiative of potentially wayward soloists. It was, of course, harder for them to control the use of their ideas as a jumping-off point for other compositions, let alone improvisations, and the mid-20th century development of graphic scores, and even “scores” that were merely sentences, gave performers so much discretion that the credit due to the composer became a moot point. This was an issue that arguably reached its most intriguing (and perplexing) manifestation with Karlheinz Stockhausen and the pieces he labelled intuitive music. Despite the gnomic nature of many of his verbal scores, entirely devoid of traditional notation, leaving musicians with the knotty conundrum of how to realise them in sound, performances somehow ended up readily identifiable as the work of Stockhausen.

Max and Stefano are, of course, both composers and performers here, and they prefer to use the term instant composition rather than improvisation for what they do: “In our view there is a difference between improvisation and instant composition. Real improvisation is something free and deep at the same time, where a performer usually lives a musical experience far from traditional concepts like harmony, rhythm and form, especially without any kind of limitation. In our case it’s better to talk about instant composition because we have a ‘score’ to follow and this score is just morphological … it says only ‘where’ to go but not ‘how’, and can be made by notes, or words, or diagrams, etc.”

There are, however, some free improvisations here, inspired by Aristotle’s analysis of the essences of drama: Mythos (plot), Ethos (character), Dianoia (theme or reasoning), Lexis (diction/speech), Melos (music) and Opsis (spectacle). The almost architectural underpinning progression of Mythos deftly suggests the exposition of a story; the introspective, delicate interaction on Ethos with its brief passage of more fretful playing, conjures the subtlety and sometimes contradictory nature of temperament. Dianoia evokes the Platonic view of the concept, discursive and perhaps rather technical; the sparkling upper-register parts and the bluesy bass lines of Lexis draw us into an animated and sometimes slightly argumentative conversation. The mystical Opsis is unexpectedly un-dramatic and non-visual, full of intriguing textures; the suitably-lyrical two-part Melos starts out tentatively, lingering over resonances and delicate phrases, though hints of anxiety and a degree of menace surface in the second part before a serene yet emotionally ambiguous conclusion.

The duo’s reading of that one-time test-piece for tenor saxophonists, Body and Soul, the only “standard” in this set, is particularly intriguing for the sonorities, the players’ re-configuration of the harmonies rendering this familiar old war-horse mysterious and unpredictable.

Of the other pieces, the “instant compositions”, Querendo Dançar draws on a Giga by John Bull found in a compilation of keyboard pieces from a golden age of English music, the late 16th and early 17th century. The Fitzwilliam Virginal Book (so called since it has been in the custody of Cambridge’s Fitzwilliam Museum for the last two centuries) was also a source of inspiration to the MJQ’s John Lewis, and prompts some of the most complex textures on this album, managing to meld echoes of the Tudor era with a severe 20th-century harmonic sensibility. The nimble, sparkling Folksong, Clowns and Litany references a string-quartet piece which Stravinsky transcribed for orchestra as well as four hands on one piano. The title track certainly flows, reflecting Copland’s comment that was its ultimate inspiration, but it also floats, flies, glides and ripples with echoes of American and French impressionist music.

The distinguished and adventurous saxophonist Steve Lacy once said: “In composition you have all the time you want to decide what to say in 15 seconds. In improvisation you have 15 seconds.” He also opined: “It is in collaboration that the nature of art is revealed.” This is certainly true of improvisation, where co-operation and submersion in the persona of the collective entity produces the best results. Listening to each other is important – even in the sonic cage-fighting characteristic of many performances by the fearsome saxophonist Peter Brotzmann and his disciples the participants pick up elements from each other and run with them – and Max and Stefano demonstrate time and again how adept they are at improvising complex lines without getting tangled up or damaging the other’s contribution. This is duo playing that eschews one-dimensional virtuosity, displaying instead a warm, subtle, contemplative and aesthetically-rewarding musical vision.

Barry Witherden

“The Long Line shows the resourcefulness of two inventive artists, who, rather than being confined by genre, constantly reshape their music.”

All About Jazz – Karl Ackermann / 13 June 2019

“… splendid improvisation… quite magnificent.”

Kudojazz Blog / 21 June 2019

“… superb collaboration… remarkable synergy… startlingly original…”

Textura / July 2019